Return to Eden

The man behind the

Wildlands Project defends his plans.

By Tim Findley, Range

Magazine fall 2003 edition

One man’s fantasy may be

another man’s nightmare. In the sparks

shooting up from a campfire and floating in

red and amber dots against a black sky is

primitive imagination born. Some of it is

about the future and adventure yet to be

had, but more of it calls to mind something

primeval and nearly forgotten, crackling

against infinity.

By one account at least

it is said to have been in such a setting in

Arizona in the early 1980s when David

Foreman expressed his Wildlands vision, for

emphasis spinning into the air a freshly

emptied tequila bottle that witnesses swear

was never heard to fall back to earth.

It is a tale no less

believable than the relentless project

Foreman set in motion that is spinning still

on the political horizon, more apparent and

even more incredible than any campfire yarn.

It would revert as much as 50 percent of the

continental United States to a pre-Columbian

condition, absent of roads and towns,

dominated in their realm by predators such

as grizzly bears and wolves that would be

free to roam in wide corridors from the

Yukon to the Yucatán. What few human beings

who might find their way into its depth

would be intruders, and the least capable of

all species at surviving in the savage

preserve.

Spinning and spinning,

the dream still sends no sound of dropping

back to reality. In fact, at least two

measures introduced in Congress, and scores

of other smaller federal and nonprofit

acquisitions have already begun to create a

map of the unbelievable, drawing a huge

portion of the world’s most successful

civilization slowly back into at least the

15th century.

Foreman, the founder of

Earth First! and the self-identified

eco-terrorist for his "monkey wrench"

tactics of spiking harvestable trees and

threatening other uses of "public" land,

could himself be relegated to credibility

only among the young extremists who dote on

his renegade image. But it was not the

blustering, bottle-pitching Foreman who

really defined the unimaginable to the

susceptible power brokers capable of making

it happen. It was Reed Noss.

With a Ph.D. in wildlife

and range sciences from the University of

Florida, 50-year-old Noss carries a résumé

thick as a country phone book, full of

publications and academic honors, faculty

positions and references from many of the

most prominent research facilities and

recognized scientists in the United States.

If not near the pinnacle of his profession

as a conservation biologist, he is watched

as a still-young "comer" from his position

at the University of Central Florida and his

increasingly high-profile role as chief

scientist and cofounder of the Wildlands

Project.

Not so nearly inclined as

Foreman to be tossing tequila bottles at

campfires, he nevertheless projects a young

and enthusiastic presence in his speeches

propounding the "re-wilding" of America.

Evidently fit, slim, and eager to coach his

students, to this reporter at least, he

seems to bear a curious resemblance to

"gonzo" writer Hunter Thompson. No one else,

he said, has ever made that comparison.

We at Range don’t mean to

imply such a mad-genius image. Noss is a

serious, recognized scientist. He agreed to

answer a series of questions conveyed to him

by e-mail about the Wildlands Project and

its intentions. We agreed to publish those

questions and answers without editing or

internal comment.

Believe it or not,

however, the Wildlands Project is a fully

staffed and funded organization based in

Washington, D.C., that works interactively

with other environmental organizations.

"Human activity is

undoing creation," says the official mission

statement of the Project. Its adherents

believe there is underway now a "sixth major

extinction event to occur since the first

large organisms appeared on earth a

half-billion years ago." The only way to

halt that "extinction event," the statement

suggests, is to dramatically limit human

activity.

"We seek partnerships

with grassroots and national conservation

organizations, government agencies,

indigenous peoples, private landowners, and

with naturalists, scientists and

conservationists across the continent to

create networks of wildlands from Central

America to Alaska and from Nova Scotia to

California."

Dr. Noss does not regard

this as a fantasy or a nightmare. We suggest

you judge for yourself.

Q&A

Reed Noss discusses the

Wildlands Project.

Range: Let’s start with the most

difficult aspect of the Wildlands Project.

Even a cursory look at the ambitions of the

plan suggests that thousands of people,

including whole communities in the West,

would have to be relocated to accommodate

these corridors and cores. How do you think

you could accomplish that?

NOSS: The most difficult aspect

of the Wildlands Project, Tim, is that there

are unethical people out there perpetrating

ridiculous lies in an attempt to discredit

us. The Wildlands Project has never proposed

relocating people to accommodate our reserve

designs. This has never been part of our

plans. Nevertheless, certain folks in the

Wise Use Movement have fabricated maps,

attributed them to us, and circulated them

to rural newspapers, websites, and so on,

apparently intending to frighten local

people and turn them against conservation.

There is even a phony web page posing as the

Wildlands Project and making us look 100

times more radical than we ever dreamed of

being. After we took legal action, that site

can no longer claim to be the official

website for the Wildlands Project.

Our proposals for

wildlands network designs in the West are

focused on public lands. For areas of

identified high conservation value within

these lands, we recommend increased

protection (i.e., wilderness status or

equivalent). Those relatively few private

lands identified as core areas are lands

belonging to The Nature Conservancy, land

trusts, conservation-minded ranchers, and

other folks who voluntarily manage their

lands for conservation. Any other private

lands that show up in our designs are

labeled "areas of high biological

significance," "compatible-use lands,"

"conservation opportunity areas," or

whatever, and are areas where acquisition,

easements, or management agreements would be

pursued with willing landowners only. The

Wildlands Project is no different from other

conservation organizations these days,

public or private, in the conservation tools

we employ or propose. I say "propose"

because the Wildlands Project works mostly

with local groups, land trusts, etc., to

implement our plans. We don’t have the money

or the political power to do it all

ourselves. We differ from many other groups

in the particularly high value we place on

wildness.

Range: "Peer review," as you say,

supports the necessity of this habitat

restoration in order to head off what

Michael Soulé says is the impending "sixth

major extinction." Yet your emphasis is on

wolves and grizzly bears, neither of which

appear to be endangered as a species. Why do

you believe it is necessary to extend their

domain at the price of human civilization?

NOSS: Actually, although we

emphasize carnivores (and not just wolves

and grizzly bears) in our literature, our

wildlands network designs are based on

multiple biodiversity conservation goals.

Our plans attempt to accomplish four major

objectives: (1) represent all native

ecosystems across their natural range of

variation in protected areas; (2) maintain

viable populations of all native species;

(3) sustain ecological and evolutionary

processes within a natural range of

variability; and (4) build a

conservationnetwork that is adaptable and

resilient to environmental change. These

goals are very well accepted within the

conservation and scientific communities.

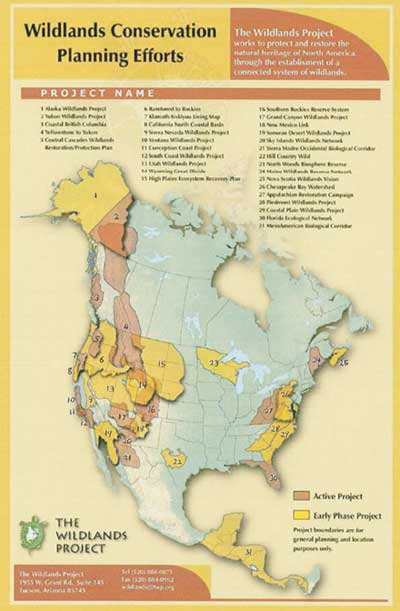

Like blobs of melting ice cream, the areas targeted by

the Wildlands Project seem to slowly

expand and run together to cover ever

more land. Why not the center of the

country? Dr. Noss says states such as

Iowa and Illinois have too little

natural habitat left, so "we have to set

the standards lower." This map no longer

appears on the Wildlands Project

website. |

We place special emphasis

on carnivores and other demanding and

ecologically important species for several

reasons. First, if you want to maintain all

native species in a region, you need to give

extra attention to those that are most

sensitive to human activities. Otherwise,

they’ll be lost. At a regional scale of

planning, carnivores make excellent focal

species because they are sensitive to the

area and configuration of habitats. They are

also vulnerable to persecution by people.

Second, scientific research (and yes, "peer

reviewed") has demonstrated that in many

cases carnivores function as keystone

species, which control the abundance of

their prey and contribute to the diversity

of the ecosystem as a whole. Third,

carnivores are emblematic of wildness,

something that is spiritually and

aesthetically important to many people, but

which is lacking in so much of the modern

world. However, it is incorrect to suggest

that the survival of carnivores is

incompatible with human civilization. Humans

have lived with carnivores for millions of

years. In some places, however (in

particular, most of the conterminous 48

states), we have hunted them to regional

extinction. I, for one, think that is

morally wrong. These creatures have as much

right to be here as we do.

Range: You have said that these

wilderness corridors and core areas would

encompass 50 percent of the continental

United States, primarily west of the 100th

meridian. Doesn’t this suggest a cultural

bias?

NOSS: Fifty percent is an

estimate I made years ago of the proportion

of an average region that would need to be

managed for conservation in order to meet

well-accepted conservation goals. The

question "how much is enough?" should be

answered empirically rather than

dogmatically. If we consider empirical

research on this question, it turns out I

was pretty much on the mark with my 50

percent hypothesis. Studies done by

researchers in North America, Australia,

Africa, and elsewhere have found that’s

about what it takes. Most of the estimates

fall in the range of 25 to 75 percent. It

takes more land in some regions than in

others to meet the same goals, because

regions differ in their biogeography. For

example, regions with high endemism (that

is, many narrowly distributed species), such

as much of California, require more area to

meet the goal of representing populations of

all species in a reserve network than a

region with more widely distributed species,

such as the northern Rockies. And, of

course, states such as Iowa and Illinois

have so little natural habitat left (only

around 2 to 3 percent) that opportunities

for meeting conservation goals are limited

without extensive habitat restoration. We

have to set the standards lower.

The Wildlands Project,

however, does not restrict its vision to

areas west of the 100th meridian. We and

other conservationists have ambitious plans

for the East as well. For example, state

government agencies in Florida and New

Jersey, of all places, are attempting to

protect a third or more of their land in

conservation areas. That’s much more than

most western states that have much more

public land.

Range: Such a radical proposal

attached to the "shock value" tactics of

David Foreman and Earth First! might be put

aside as fantasy, but you place substantial

scientific credentials of your own in

conjunction with what many regard as the

demagogic terrorist methods of Foreman. Are

you comfortable with that?

NOSS: Well, Tim, the Dave Foreman

of the 1980s Earth First! days was a bit

different from the Dave Foreman of today.

Isn’t that true of anyone? His conservation

goals remain basically the same (I generally

agreed with him then and I agree with him

now), but his tactics have changed.

Curiously, Dave’s a lifelong Republican.

He’s hardly a terrorist, and I resent your

use of that word. Save the terrorist word

for murderers like Osama bin Laden and

Timothy McVeigh.

I came into the

conservation movement as a naturalist, one

who studies nature. I saw the beautiful

woods I played in as a kid in southern Ohio

destroyed by developers. I went to college

to become a biologist, hoping to apply my

skills to the conservation of nature. Today

we call this field conservation biology,

which I define as science in the service of

conservation. Conservation biology is

mission oriented, as are medical science,

range science, engineering, and other

applied sciences. We are interested in

solving problems, not just knowledge for the

sake of knowledge. Many prominent

conservation biologists and other scholars

have served on the board of the Wildlands

Project, and many more (at least thousands,

I would guess) are very comfortable with our

approach. Indeed, one reason we founded the

Wildlands Project was to forge a link

between activists and scientists interested

in large-scale conservation.

Range: Clearly the acquisitions

of public and private lands appropriate to

the Wildlands plan is ongoing by funded

conservation trusts led by The Nature

Conservancy. Is TNC in part clearing the way

for such connectivity and what you call

"linkages" in the West?

NOSS: TNC has their own

ecoregional plans; they don’t follow ours.

However, it is true that over the last few

years, TNC’s planning has taken on a

regional focus much like ours, and they use

many of the same scientific methods. I think

it’s clear that the Wildlands Project has

had a significant influence on TNC and other

major conservation groups. In addition,

research in conservation biology has

demonstrated that a collection of small,

isolated reserves (TNC’s old approach) just

doesn’t cut it in the long term—you need

large, interconnected networks of protected

areas. Small, disconnected reserves lose

native species rapidly over time, are

invaded by alien weeds, and are more

difficult and expensive to manage. Most

private land trusts, on the other hand, have

shown little interest in biology—they’ve

been more interested in protecting "open

space." But that’s beginning to change as

these organizations get better educated

staffs.

Range: As you have observed in

speeches, the primary danger today even to

such major predators as wolves and grizzly

bears is not hunting, but roadkills. Are you

suggesting in this project that even

transcontinental highways be altered in some

way or closed to accommodate the corridors?

NOSS: In some regions, even

surprising places such as the central

Canadian Rockies, direct roadkill is the

largest documented source of mortality for

large carnivores. However, in many other

places, human persecution (legal or illegal

hunting) remains the major cause of death.

But here, too, roads figure prominently in

the problem, because they provide access to

people with guns. The higher the density of

roads, the lower the probability that

wolves, bears, and other animals can

survive. This has been documented worldwide.

Regarding major highways,

we are not so impractical to suggest they be

closed. However, we do recommend

underpasses, land bridges, and other

wildlife crossings be constructed at

strategic locations—places where animals

regularly get struck—to protect wildlife as

they move across the landscape. New highways

should be built only if they take the

movement needs of wildlife into account.

Wildlife crossings have been built in

several states, for example Colorado,

California, and Florida, as well as

extensively in Europe. Yes, it’s costly, but

not close to the cost of building the road

in the first place. Ironically, in some

cases building a new road can be a good

thing. Near where I live in Florida, the

state is proposing to build a new

limited-access highway that will be elevated

for seven miles to protect black bears,

other wildlife, and sensitive wetlands. The

new highway will replace a busy two-lane

road that is responsible for most of the

black bear roadkills in the state.

Range: Do you not agree that the

economic impact of such a project would be

disastrous to the western United States and

even to the nation as a whole?

NOSS: Absolutely not. The cost

would be trivial compared to many things our

society spends big money on (for example,

welfare, missiles, and highways). In many

cases wilderness preservation enhances local

economies by stimulating tourism and

business investments and relocations. This

has been demonstrated convincingly by

Professor Tom Power at the University of

Montana, among others. Reintroducing wolves

to Yellowstone has given the local economy a

shot in the arm. The state of Florida has

been spending more than $300 million per

year for nearly two decades buying land for

conservation, so that the state will remain

attractive to tourists and businesses.

Range: Assuming such a plan is

implemented, who would administer and manage

it? The government? Or a nongovernment

agency? Who should have police powers in

controlling use?

NOSS: We’re not talking about any

kind of centralized administration and

management of wildlands networks. Despite

the claims of the wise-use alarmists on the

internet, we are in no way aligned with the

United Nations and their fictitious black

helicopters. To the extent that new

wilderness areas, national parks, national

wildlife refuges, etc., are added to the

system, they would be managed by the federal

agencies in charge, as they are today. Other

lands would be managed by land trusts, other

private organizations, or by the same

willing landowners (ranchers, farmers, and

others) who manage them today. But we think

there should be added incentives, such as

big tax breaks, for managing land in a way

friendly to nature. There would be no

"police power" other than the law

enforcement system already in place.

Range: Did you once say that

westerners are part of the "slothful and

ignorant populace" who disagree with you? Do

you not recognize the elitism contained in

the proposal itself?

NOSS: I don’t remember saying

that, but if I did I would have been joking.

I wouldn’t use the word "slothful" in a

derogatory sense, because I like sloths. On

the other hand, I do believe that ecological

ignorance on the part of the public is one

of our greatest problems. Most people,

particularly in the cities, don’t have a

clue how nature operates. However, this

problem is hardly unique to the West. In

fact, studies have shown that easterners are

more ignorant about wildlife, on average,

than westerners. As for elitism, if it is

elitist to place a high value on ecological

education and on compassion for the land and

living things, then yes, I’m an elitist. But

I certainly don’t hold any special grudges

against westerners. I’ve spent most of my

professional career in the West and the

South, where I feel more comfortable than

with uptight easterners.

Range: What if you’re wrong? None

of us may live long enough to know, but what

if species are more adaptable than you seem

to think? What if the growing general

acceptance of ecological relationships

assures a natural balance in the future

better than any imposed plan could do? And

what, conversely, if such enforced

intervention as the Wildlands Project leads

to ultimately dire consequences on social

freedom: do you care about that?

NOSS: I do care. The proposals of

the Wildlands Project are science based. But

even the best science (which we strive for)

carries a moderate-to-high level of

uncertainty. Sure enough, some research

suggests that particular species are more

adaptable to human activities than we once

thought.

The pileated woodpecker,

for example, declined with forest

fragmentation across much of the country,

but now seems to be doing fairly well in

fragmented landscapes, as long as enough big

trees are around for foraging and nesting.

It adapted. However, probably more species

are turning out to be more sensitive to

human landscape modification than we

thought, but we won’t know for sure unless

we monitor their populations across many

generations. In the face of such

uncertainty, scientists recommend following

the precautionary principle, where we try to

pursue policies and management practices

that pose the least risk to nature and human

society. Sometimes there are conflicts, of

course, and trade-offs must be made. The

available evidence suggests that the

extinction crisis is our greatest global

problem. Therefore, in the face of

uncertainty I would risk erring on the side

of protecting too much land rather than too

little.

Although this may

conflict with economic development in some

cases, it need not conflict with personal

liberties. Big corporations pose a much

greater threat to liberty than

conservationists. Like many in the Wildlands

Project, I consider myself a conservative—an

old-style, Teddy Roosevelt-kind of

conservative. I’m libertarian in many of my

views, especially with respect to personal

behavior. For example, it’s my own damn

business whether or not I wear a seat belt.

But given the high level of selfishness that

humans display, we need policies and laws to

protect nature, just like we need laws to

protect human life and dignity from the

depredations of other humans.

Range: Certainly as an optional

question for you, but one still most

troubling for many: statements by Foreman

and others have suggested that returning so

much area to a pre-Columbian state can only

be accomplished by some form of population

control, bluntly eliminating some portion of

human existence. This is a chilling

statement with obvious derivations. Can you

comment on it?

NOSS: I don’t think the

implications are so obvious, Tim. Globally,

human population growth is the biggest

threat to nature and to human liberty and

peace. Second in importance is the growing

rate of per capita resource consumption.

What kind of world do we want to live in? A

world with swarming people pressed shoulder

to shoulder or a world with wide open spaces

and clean air to breathe? Population control

need not require draconian measures—in fact,

I would oppose such measures. Rather, it’s a

matter of providing incentives and

disincentives. Rather than giving people tax

breaks for every additional child they

have—which we do now and President Bush

wants to increase—I would favor tax breaks

for those couples with two or fewer children

and tax penalties for those with three or

more. I think such a tax policy, combined

with strict limits on immigration, would

take care of our population problem in the

United States. Likewise, destructive

technologies (for instance, those wasteful

of fossil fuels) should be taxed heavily and

sustainable technologies, such as solar and

wind energy, should be promoted.

"Conservative" and "conservation" spring

from the same root, and it’s about time

today’s so-called conservatives figured that

out.